Three-dimensional continuum element library

Three-dimensional continuum elements can be hexahedra (bricks), wedges (triangular prism), or tetrahedra.

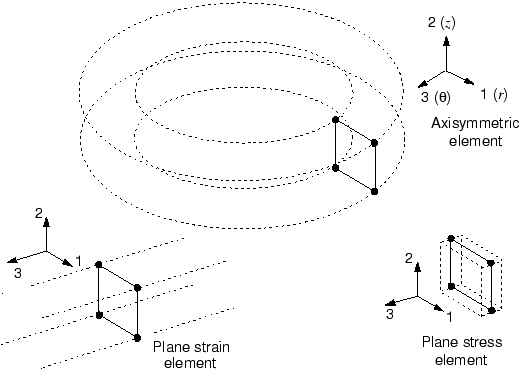

A library of solid elements also includes two-dimensional elements. The most commonly used two-dimensional continuum elements are as follows:

- Plane strain elements suitable for modeling thick structures (out-of-plane strain is zero); for example, a cross-section of a dam under water pressure.

- Plane stress elements suitable for modeling thin structures (out-of-plane stress is zero); for example, thin slabs with one dimension smaller than the other two.

- Axisymmetric elements suitable for analyzing structures with axisymmetric geometry subjected to axisymmetric loading; for example, an O-ring pressed into a groove by a top plate.