Material Classification | ||

| ||

Isotropic materials have identical properties in any direction and are characterized by two independent material constants (Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio). Most metals (steel, aluminum) are isotropic materials.

Homogeneous materials have consistent properties throughout the volume. That means that any impurities, localized changes due to heat or other processing effects, and internal voids that reduce the inherent stiffness of the material are not accounted for. You must keep these approximations in mind when you assess your simulation results.

Anisotropic materials have different properties depending on the direction and require you to specify the material orientation. Materials such as wood and fiber-reinforced composites are very anisotropic; they are much stronger along the direction of grain (or fiber) than across it.

Orthotropic materials belong to a special subtype of anisotropic materials. Othrotropic materials exhibit different behavior in three orthogonal planes (three mutually perpendicular material directions). Nine independent elastic stiffness parameters (Young's modulus, Poisson's ratio, and shear modulus in three principal material directions) are needed to define an orthotropic material.

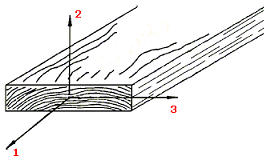

Wood is an example of an orthotropic material. The material properties of wood are described in the longitudinal, radial, and tangential directions. The longitudinal axis (1) is parallel to the grain (fiber) direction; the radial axis (2) is normal to the growth rings; and the tangential axis (3) is tangent to the growth rings.

The following common material properties apply to FEA applications:

- Elastic Modulus or Young's Modulus

-

Measures the stiffness of a material and its ability to resist loads. For a linear elastic material the elastic modulus in a certain direction is defined as the stress value in that direction that causes a unit strain in the same direction (the slope of the stress-strain curve in the elastic region).

For example, a one inch bar of a material with Young’s modulus of 35 million psi elongates by one thousandth of an inch under a tensile load of 35 thousand psi.

- Shear Modulus or Modulus of Rigidity

- Measures the ability of a material to resist shear loads. It is the ratio between the shearing stress in a plane divided by the associated shearing strain.

- Poisson's Ratio

When a material extends in the longitudinal direction, it usually tends to contract in the lateral directions (similarly, when is compressed in one direction, it usually expands in the other two directions). If a body is subjected to a tensile stress in the -direction, then the Poisson’s ratio, , is defined as the ratio of lateral contraction in the -direction divided by the longitudinal strain in the -direction.

Most materials have Poisson's ratio values ranging between 0.0 and 0.5. Some materials (like polymer foams) have a negative Poisson’s ratio; when these materials are stretched in one direction, they expand in the lateral directions.

- Coefficient of Thermal Expansion

Measures the fractional change in size (length, area, or volume) per unit change in temperature at a constant pressure. Materials generally expand in all directions when subjected to a temperature increase.

Depending on which dimensions are considered when measuring changes in size per unit change in temperature, there are definitions of volumetric, area, and linear coefficient of thermal expansion.

- Thermal Conductivity

- Measures the effectiveness of a material in transferring heat energy by conduction. It is defined as the rate of heat transfer through a unit thickness of the material per unit change in temperature.

- Density

- Mass per unit volume.

- Specific Heat

Measures the quantity of heat required to raise the temperature of a unit mass of a material by one unit of temperature.

The relationship between heat and temperature change is expressed in the form: Heat = Specific Heat * mass * (temperature change)

FEA applications typically offer material libraries that include most standard materials. The reported nominal material properties are accepted average values taken from many tests. When you accept a tabulated property value as a single number to be used in a simulation, keep in mind it actually has a probability distribution associated with it. For example the Young’s modulus for steel has a standard deviation of approximately 7.5%. Most material tests yield results that follow a normal curve (or “bell shaped”) distribution. If your part is made of a less predictable material, you need to consider the variability of the material properties in the total factor of safety of your design.