Element Geometry

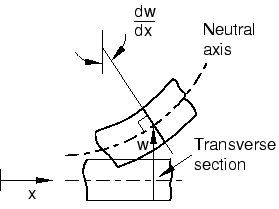

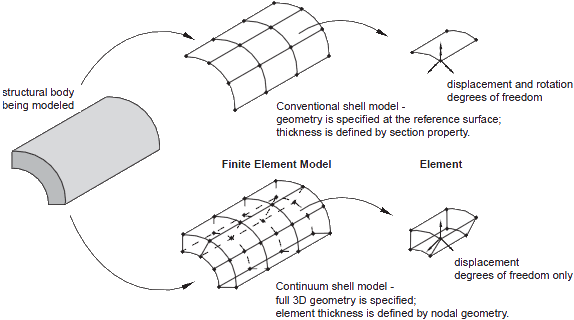

Conventional shell elements (2D elements) discretize a reference surface by defining the element's planar dimensions, its surface normal, and its initial curvature.

The nodes of a conventional (2D) shell element, however, do not define the shell thickness; the thickness is defined through section properties and must be specified. Continuum shell elements, by contrast, resemble three-dimensional solid elements in that they discretize an entire three-dimensional body, yet are formulated so that their kinematic and constitutive behavior is similar to conventional shell elements. Continuum shell elements (3D elements) are more accurate in contact modeling than conventional shell elements, since they use two-sided contact taking into account changes in thickness. For thin shell applications, however, conventional shell elements provide superior performance.

The shell thickness is required to describe the shell cross-section and must be specified. For linear elastic material behavior, the stiffness of the cross-section is calculated only at the beginning of the simulation. Three section points through the thickness of the shell: bottom surface, the midplane, and the top surface provide efficient results accuracy for stress and strain output.