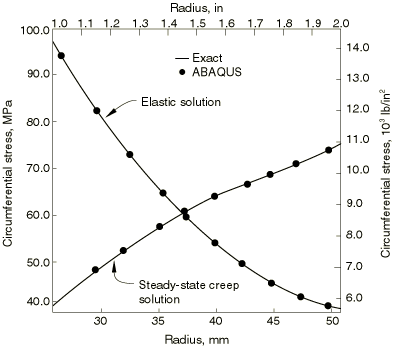

The cylinder is subjected to a rapidly applied internal pressure of 60 MPa

(8700 lb/in2) that is held constant for a long period of time, so

that the steady-state creep conditions are reached.

The initial application of the pressure is assumed to occur so quickly that

it involves purely elastic response, which is obtained by using the static

procedure. The creep response is then developed in a second step, using the

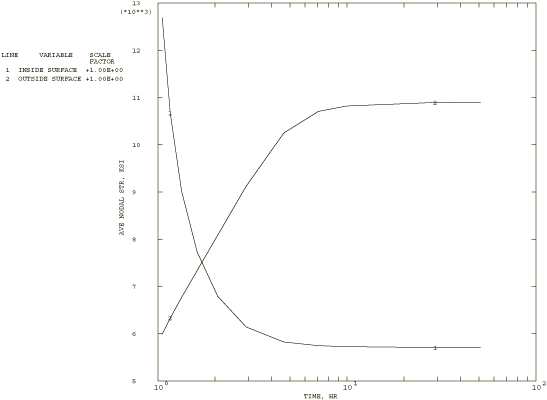

quasi-static procedure. A response of 180,000 seconds (50 hours) is requested,

which is sufficient to reach steady-state conditions. During the quasi-static

step a tolerance is required to control the time increment choice and, hence,

the accuracy of the transient creep solution. In this case we assume that

moderate accuracy is required. Errors in stress of about 0.7 MPa (100

lb/in2) will make a small difference to the creep strain added

within an increment. Converting this stress error to a strain error by dividing

it by the elastic modulus gives a tolerance of 5 × 10−6. Higher

accuracy in the integration of the creep constitutive model can be obtained by

reducing this tolerance, at the expense of using more time increments.

Alternately, using a large tolerance value will allow

Abaqus

to use the largest possible time increments, so that low accuracy will result

during the transient, but the steady-state solution will be reached at minimum

cost. Thus, if the steady-state solution is the only part of the solution of

interest, it is effective to set the tolerance to a large number.

With the tolerance specified in the quasi-static procedure,

Abaqus

uses automatic time incrementation. The scheme is rather simple and aims at

increasing the time increments gradually as the solution progresses toward

steady state. In a small-displacement case such as this, explicit integration

of the creep constitutive model is usually efficient because the method is

inexpensive per time increment (since no new stiffness matrix needs to be

formed and solved), and its stability limit is usually quite large compared to

times of interest in the solution. The automatic time stepping scheme includes

an internal calculation of the stability limit, and the time increment is

controlled to remain within this limit. If this is too restrictive—if it

results in a sequence of time increments that are all much smaller than the

remaining part of the time period requested on the data line associated with

the quasi-static procedure (10 successive increments where the time increment

is less than 2% of the remaining time period)—Abaqus

automatically switches to an implicit time integration scheme that is

unconditionally stable. The only limit at all on the time increment selection

is then accuracy as specified by the tolerance. This switch to implicit

integration can be suppressed by the user in the quasi-static procedure. In

this example the switch to implicit integration occurs at increment 44, after

27,108 seconds (7.53 hours) of creep. This allows

Abaqus

to choose large time increments (up to 39,600 seconds, or 11 hours) toward the

end of the solution.