Problem description

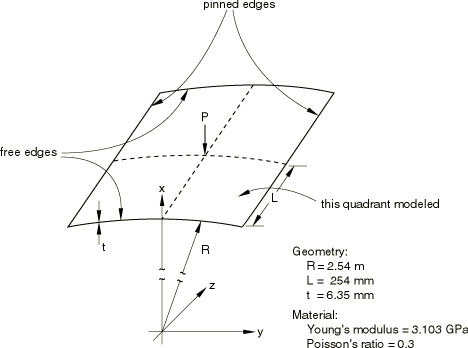

The dimensions of the roof are shown in Figure 1. The material is linear elastic, with a Young's modulus of 3.103 GPa and a Poisson's ratio of 0.3.

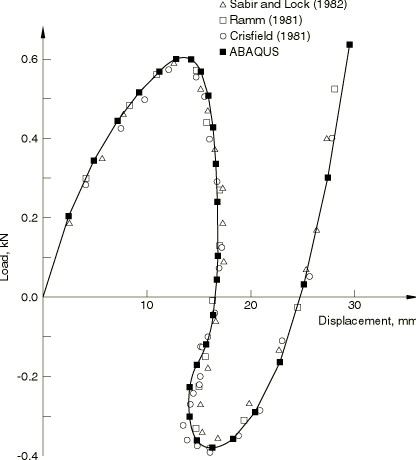

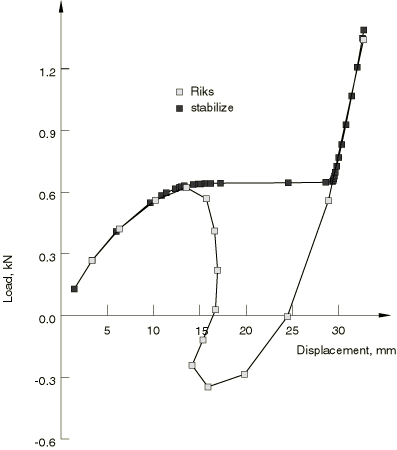

ProductsAbaqus/Standard Problem descriptionThe dimensions of the roof are shown in Figure 1. The material is linear elastic, with a Young's modulus of 3.103 GPa and a Poisson's ratio of 0.3. Modeling and solution controlThe roof is assumed to deform in a symmetric manner, so one quadrant is discretized, as shown in Figure 1. We use two regular 6 × 6 meshes of shell elements, one of type S4R5 (4-node elements with one integration point) and one of type S4R (finite membrane strain shell element), and an 8 × 8 mesh of triangular shell elements of type S3R. In addition, two regular 6 × 6 meshes of continuum shells are provided, one of type SC6R (finite membrane strains, in-plane continuum shell wedge) and one of type SC8R (finite membrane strains, hexahedron continuum shell). No mesh convergence studies have been performed, but the comparison of the results given by these meshes with published numerical solutions suggests that, at least with respect to load-deflection behavior, these meshes give reasonably accurate results. When using the modified Riks method, the load magnitude and suggested initial increment size should provide a reasonable estimate for the sense and magnitude of the first increment in load. It is known that the critical load for this case will not exceed 750 N. With an initial time step of .025 for a time period of 1.0, we give a load of 3000 N. This implies an initial load increment of about 75 N on the entire roof. Furthermore, we are not interested in postsnap behavior much beyond the magnitude of the critical load, so we terminate the analysis when a load proportionality factor of 0.06 has been reached. This corresponds to a total load on the entire roof of 720 N. In this problem the static equilibrium load actually reverses direction as the roof goes through an unstable snap. The modified Riks algorithm is able to track such load reversals. Gauss integration is used for the shell cross-section. When using the volume proportional damping capability, a total load of 1332 N is applied, which is roughly equivalent to the load at which the Riks method analysis stops. The initial load increment is 10 percent of the total load. This algorithm does not capture load reversals; when such reversals would occur, the structure accelerates and the increased velocity produces enough viscous forces to balance the externally applied load. As a result, the external load stays almost constant during the unstable part of the deformation. Results and discussionFigure 2 shows the downward vertical displacement of the point under the load (the middle of the roof) and of the midpoint of the free edge of the shell as functions of the applied load on the entire roof. The roof collapses unstably at a load of about 600 N, with the equilibrium load falling rapidly to a value of about −380 N as the snap-through occurs. During the latter part of the snap-through the middle point of the roof moves upward slightly (snaps back) from a displacement of about 16.8 mm to 14.1 mm just before the end of the snap-through. Following snap-through, the shell stiffens rapidly as the load increases, as would be expected. In the original, unloaded configuration, the centerline of the roof rises about 12.7 mm above the pinned edges. From Figure 2 it can be seen that the instability occurs when the point being loaded has a downward displacement of about 14.4 mm, when it is just below the horizontal plane defined by the pinned straight edges. However, at this point of instability, the point in the middle of the free edge has only displaced downward by about 3 mm. At the end of the snap-through the point under the load has displaced about 16.3 mm, while the middle of the free edge has displaced about 26.3 mm. Thus, during the snap the point under the load moves a total distance of only about 2 mm, while the middle of the free edge moves 23.3 mm. Several authors have investigated this same problem (see the references at the end of this example) and have obtained results that agree fairly closely with those obtained here. Figure 3 shows a comparison of these various solutions for the variation of load with displacement of the point under the load. Figure 4 shows a comparison of the Riks method and the automatic stabilization method (volume proportional damping) in terms of the downward vertical displacements of the point under the load as functions of the applied load. While the deformation is stable (that is, during the initial loading) and after the snap-through takes place, both curves are very similar, which means that the damping introduces negligible dissipation. However, during the snap-through the strain energy that the structure wants to relieve in going from one stable configuration to the next is dissipated through damping instead of through decreasing the load. The disadvantage of this method is that it produces an almost constant loading without giving information on how far from a static equilibrium state it is (that is, how severe the snap-through is). On the other hand, this method still works when instabilities are local, in which case the Riks method may fail. Input files

References

Figures    | |||||||