Plasticity | ||||

|

| |||

Plasticity theories model the material's mechanical response as it undergoes such non-recoverable deformation in a ductile fashion. The theories have been developed most intensively for metals, but they are also applied to soils, concrete, rock, ice, crushable foam, and so on. These materials behave in very different ways. For example, large values of pure hydrostatic pressure cause very little inelastic deformation in metals, but quite small hydrostatic pressure values might cause a significant, non-recoverable volume change in a soil sample.

The fundamental concepts of plasticity theories are sufficiently general that models based on these concepts have been developed successfully for a wide range of materials.

Yield Criterion

A yield criterion (or yield surface) specifies the shift from elastic to plastic behavior (onset of the plastic flow) in terms of a test function that determines if the material responds purely elastically at a particular state of stress. Several yield criteria have been developed to describe different material behaviors.

For example, the Tresca's yield criterion assumes that yielding occurs when the maximum shear stress (at a material point under a general state of stress) reaches the value of the maximum shear stress when yielding occurs in a uniaxial tension test.

The von Mises yield criterion assumes that yielding occurs when the distortion energy (at a material point under a general state of stress) is equal to the distortion energy at the onset of yielding in a uniaxial tension test. The von Mises yield criterion applies best to ductile materials, such as metals.

The Drucker-Prager yield criterion describes best the behavior of geological materials that exhibit pressure-dependent yield.

Flow Rules

A flow rule specifies the direction of inelastic deformation that occurs if the material is no longer responding purely elastically. An associative flow rule considers the plastic strains to occur in a direction normal to the yield surface.

Hardening Rules

A hardening rule specifies how the loading and unloading of materials affect their yield strength during the plastic flow phase. Often the plastic deformation of the material increases its yield stress for subsequent loadings: this behavior is called work hardening.

In isotropic hardening, the yield surface changes size uniformly in all directions such that the yield stress increases (or decreases) in all stress directions as plastic straining occurs. In kinematic hardening, the yield surface remains constant in size and the surface translates in stress space with progressive yielding.

Characteristics of Metal Plasticity

The deformation of the metal prior to reaching the yield point creates only elastic strains, which are fully recovered if the applied load is removed. However, once the stress in the metal exceeds the yield stress, permanent (inelastic) deformation begins to occur. The strains associated with this permanent deformation are called plastic strains. Both elastic and plastic strains accumulate as the metal deforms in the post-yield region.

The stiffness of a metal typically decreases dramatically once the material yields. A ductile metal that has yielded will recover its initial elastic stiffness when the applied load is removed.

A metal deforming plastically under a tensile load might experience highly localized extension and thinning, called necking, as the material fails. The engineering stress (force per unit undeformed area) in the metal is known as the nominal stress, with the conjugate nominal strain (length change per unit undeformed length).

The nominal stress in the metal as it is necking is much lower than the material's ultimate strength. This material behavior is caused by the geometry of the test specimen, the nature of the test itself, and the stress and strain measures used. For example, testing the same material in compression produces a stress-strain plot that does not have a necking region because the specimen is not going to thin as it deforms under compressive loads.

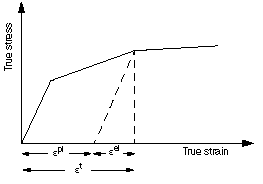

The post-yield material behavior is approximated in a FEA model with data points on a stress-strain curve that are gathered from material test data. The strains provided in material test data used to define the plastic behavior are not likely to be the plastic strains in the material but rather the total strains in the material. You must decompose these total strain values into the elastic and plastic strain components . The plastic strain is obtained by subtracting the elastic strain, defined as the value of true stress divided by the Young's modulus, from the value of total strain.

Depending on the required input format for the stress/strain curve data, you might need to convert the nominal stress and nominal strain to true stress and true strain. Although, the differences between the nominal and true values at small strains are small, there are significant differences at larger strain values; therefore, it is extremely important to provide the proper stress-strain data if the strains in the simulation will be large.

The figure below shows a nominal stress-strain curve defined by six data points.

Depending on the required input format for the stress/strain curve data, you might need to convert the nominal stress and nominal strain to true stress and true strain. Although, the differences between the nominal and true values at small strains are small, there are significant differences at larger strain values; therefore, it is extremely important to provide the proper stress-strain data if the strains in the simulation will be large.

The relationship between true strain and nominal strain is:

The relationship between true stress and nominal stress and strain is: